Lactose intolerance

POST URL:

https://mydnas.github.io/myDNA/

CONTACT

inga.patarcic@gmail.com https://github.com/IngaPa

IDEA

In this post, I will:

-

briefly introduce lactose intolerance, and

-

guide you to the myDNA lactose intolerance analysis.

What is lactose intolerance?

The ability to digest lactose as an adult is called lactase persistence. Opposite to it, a digestive disease caused by lactose malabsorption is called lactose intolerance.

Lactose is a type of sugar in milk that is processed by an enzyme lactase in our small intestine. Lactase (lactase-phlorizin hydrolase or LPH) process lactose into two other sugar types: glucose and galactose. When cells in your small intestine do not produce sufficient levels of lactase enzyme to digest all the lactose you eat or drink - lactose gets fermented by bacteria in the distal ileum and colon. Products of fermentation: hydrogen, methane and carbon dioxide cause nausea, bloating, diarrhea, gas, and/or unpleasant pain in abdomen (Olds and Sibley 2003).

The activity of lactase is maximal at birth and declines with age. Many people experience the first symptoms of lactose intolerance at young adult age. For example, I had no wish to drink milk for years. At the age of 26, after months of having problems with bloating, I finally realized I was lactose intolerant. Age at manifestation of primary lactose intolerance symptoms varies between ethnic groups (Seppo et al. 2008).

Genetic background of lactose intolerance/persistence

Lactose intolerance can be genetically or environmentally induced.

Genetically induced lactose intolerance is sometimes referred as primary lactose intolerance, adult-type hypolactasia, hereditary lactase deficiency or lactase non persistence. It corresponds to state when lactase (enzyme) is partially or fully absent in your gut and differences in lactase activity are due to genetic polymorphisms. In this case, lactose intolerance is genetically induced as a consequence of the reduction in the LCT gene expression.

As for all other genes in the human genome, a level of gene expression of lactase (LCT) gene is precisely fine tuned by specific regions in the genome - gene regulatory elements. LCT gene is regulated by nearby cis-acting elements (Wang et al. 1995). Multiple independent variants in those regions have allowed various human populations to quickly modify LCT expression (Deng et al. 2015) as an adoption to the domestication of dairy animals (Bayless et al. 2017).

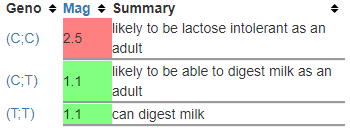

For example, rs4988235 - also known as “C/T(-13910)” or just 13910T - is a genetic polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with lactose intolerance in European Caucasian populations (Bersaglieri et al. 2004). On this position in the genome, there are two possible alleles - C and T - and three possible genotypes CC, CT and TT.

rs4988235(T) allele is associated with lactase persistence. In European populations, it is more common than rs4988235(C) allele. Individuals who have two T alleles in their genome can have TT or CT genotype and are likely able to digest milk. Individuals who have two C alleles, or CC genotype (rs4988235(C;C)) are likely to be lactose intolerant.

Important to remember is that G pairs with C (and T pairs with A) in a molecule of DNA. In other words, on locations in the genome where C alleles are, G alleles are present on the complementary strand of the DNA molecule. This is important since some companies will report alleles (genotypes) from one strand of a DNA molecule, whereas other companies report alleles from another strand.

Thus, individuals with two C alleles or two G alleles at rs4988235 are likely to be lactose intolerant.

How can I identify risk variants in my genome that are associated with lactose intolerance using myDNA R package?__

Step 1. Genotype your genome.

At the moment, the easiest way to do it is to buy a direct-to-consumer test by one of the DNA testing companies.

Step 2. Download your genotypes and store them on your computer

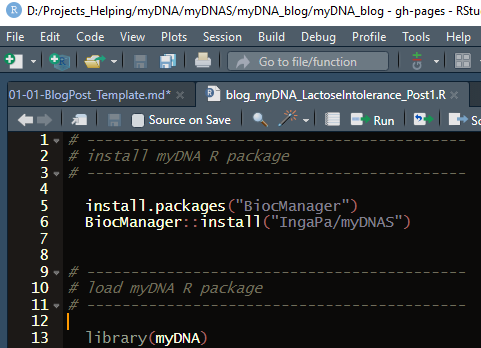

Step 3. Install R, RStudio and myDNA R package

- Install R from: here

- Install RStudio from: here

-

Learn about R and RStudio by watching this youtube video

- Open RStudio and open new RScript ( click on File -> Rscript)

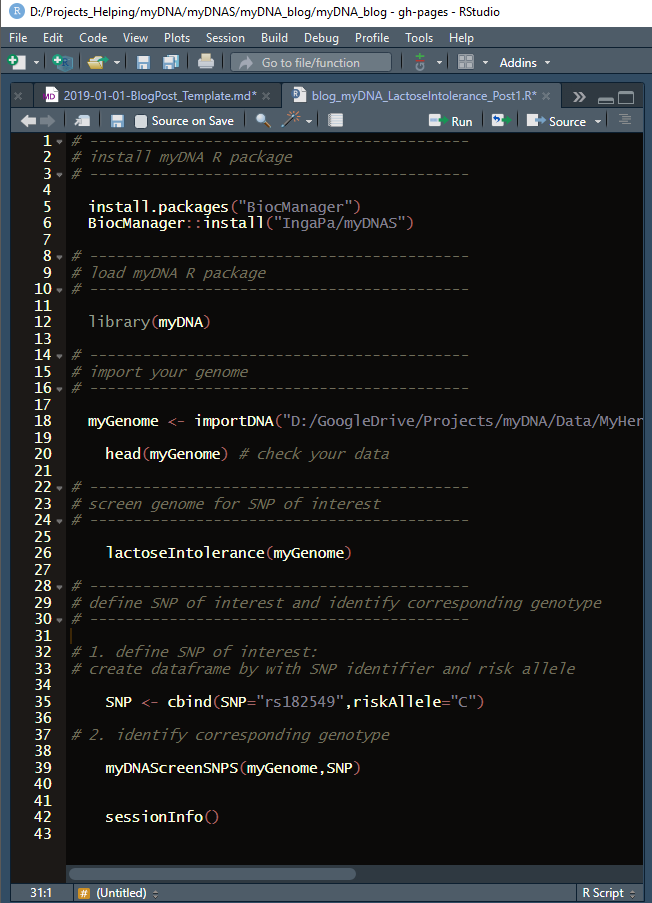

- Install myDNA R package from my GitHub account by running:

install.packages("BiocManager")

BiocManager::install("IngaPa/myDNAS")

- And import myDNA library by running:

library(myDNA)

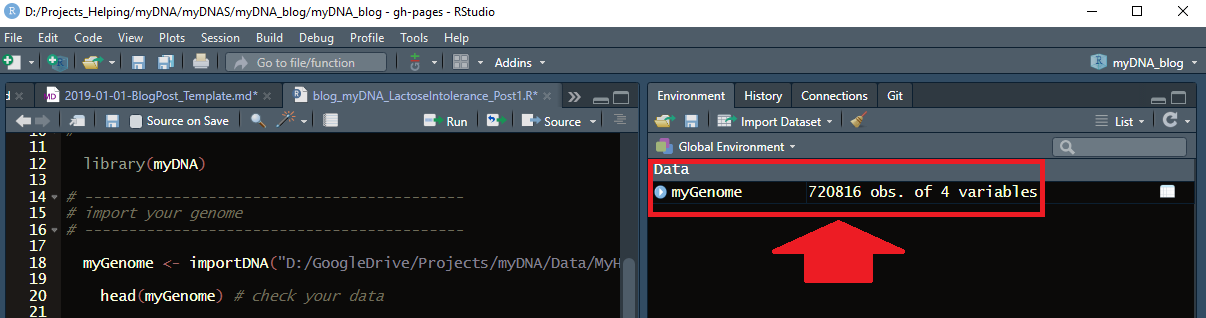

Your R session should look as follows:

Step 4. Import your genome in R by running:

importDNA("write-full-path-here")

In your R script you should type something like:

myGenome <- importDNA("/bla/Projects/myDNA/Data/MyHeritage/MyHeritage_raw_dna_dataInga/MyHeritage_raw_dna_data.csv")

Now, my genome appeared as a variable in the R environment:

Notice, it has 720,816 rows and 4 columns.

It means that 720,816 positions (SNPs) in my genome are genotyped (I “consumed” myHeritage DTC test).

For each position, I received the following info:

- unique identifier for each SNP (rsid),

- chromosome where each SNP is located,

- location on the chromosome,

- your genotype;

This corresponds to four reported columns.

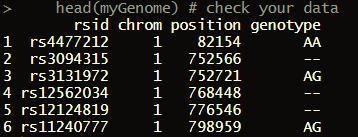

If you wish to observe imported file, you can run:

head(myGenome)

It returns:

This results mean following: For example, the first row of myGenome data table can read: SNP rs4477212 is located on chromosome 1, position 82154, and my genotype for it is AA.

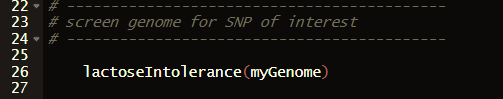

Step 5. Perform myDNA lactose intolerance analysis myDNA R package contains the lactoseIntolerance() function that for rs4988235 SNP extracts info about your genotype. By running lactoseIntolerance(myGenome) I got the following results:

By running

lactoseIntolerance(myGenome)

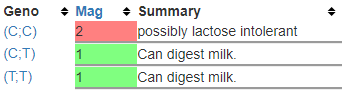

I got the following results:

Step 6. Results interpretation

myDNA lactose intolerance analysis reported that I have two G alleles for rs4988235.

Since, a) I am of European ancestry; and b) individuals who have two G alleles (or two C alleles on the complementary strand of DNA molecule) are likely to be lactose intolerant, I should be lactose intolerant as well.

Indeed, I am lactose intolerant.

I started to observe symptoms of intolerance more than three years ago. It took me a few months before I narrowed down my search and identified the culprit for my bloating problems. I do not process lactose well. Naturally, my first reaction was to eliminate all dairy products from my diet. This reduced my symptoms, but it did not remove them 100%. I kept searching for the culprit…

A year later, I read a chapter about lactose intolerance in the book written for athletes and trainers about proper food habits. It stated that the majority of hormone pills and medications are filled with lactose. Startled, I removed hormone pills from my everyday use. Whoa!!!! I was finally free of lactose-intolerance symptoms.

Limitations of the myDNA analysis

myDNA lactose intolerance analysis has 3 major limitations:

-

It is population specific.

-

Environment, microbiome and food you eat makes a difference

-

I did not cover congenital lactase deficiency

Population specific analysis

Well, I share lactose intolerance as a phenotype with many individuals across the globe. It has been estimated that approximately 65-70% of the global population is lactose intolerant in their adult age, but the exact number is unknown (Bayless et al. 2017). It is generally more prevalent in the “non-European” populations.

Until now, at least five different functional alleles associated with lactose intolerance have been identified. Association of rs4988235 with lactose intolerance is characteristic for European populations (Enattah et al. 2002). In populations of sub-Saharan Africans, the rs4988235(T) allele is so rare that it is unlikely to be predictive of lactose intolerance. Other SNPs can be predictive of lactose intolerance in several African populations instead: −13907G, −13915G, and−14010*C (Mulcare et al. 2004; Tishkoff et al 2007). T/G−13915 and T/C−3712 are associated with lactose intolerance in Arabian ethnic pastoral populations (Enattah et al. 2008).

Thus, if I wasn’t of European ancestry, I would rather test different polymorphism in my genome.

Environment, microbiome and food you eat makes a difference

Lactose intolerance has not exclusively a genetic background. Environmentally induced or secondary or acquired hypolactasia can be induced by the injury to the small intestine caused by celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, infection or other diseases (Canani et al. 2016). Thus, even if you have GG genotype at rs4988235, it does not necessarily mean you will develop lactose intolerance. Under conditions of stress, individuals might be more prone to become lactose intolerant.

On the other hand, colonic bacteria can as well adapt to chronic lactose exposure and mimic a prebiotic effect. Gut bacteria can increase fecal beta galactosidase activity and/or decrease hydrogen production and as a consequence facilitate lactose processing. Thus, regular dairy food consumption could lead to colonic adaptation by the microbiome in by lactose intolerant individuals (Levitt et al. 2013).

Congenital lactase deficiency

Unfortunately, in this post, I will not cover congenital lactase deficiency

Possible suggestions/Other approaches

So, can you overcome the aforementioned limitations of myDNA lactose intolerance analysis?

Suggestion #1

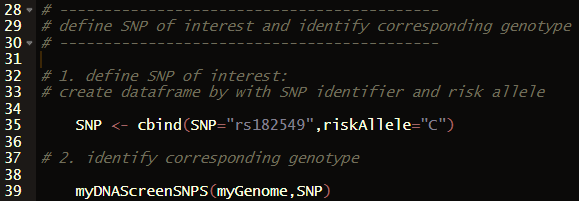

Using myDNA functions, you can play more with your genome!

For example, you can write your own piece of code to test your genome for other lactose-intolerance associated polymorphisms.

Or, you can use myDNA function myDNAScreenSNPS() to identify any SNP of interest. For example, “G/A(-22018)” corresponds to rs182549.

I will screen my genome for rs182549 by running the following lines:

SNP <- cbind(SNP="rs182549",riskAllele="C")

myDNAScreenSNPS(myGenome,SNP)

Results again indicate that I am likely lactose intolerant:

7. Where can I find more info about lactose intolerance?

You can start querying on-line bioinformatics databases such as:

OMIM,

MedGen, and

If you are interested in genetic background of lactose intolerance/persistence check: SNPedia, openSNP,…

You can also read scientific papers and follow their literature:

-

Bersaglieri, T., Sabeti, P.C., Patterson, N., Vanderploeg, T., Schaffner, S.F., Drake, J.A., Rhodes, M., Reich, D.E. and Hirschhorn, J.N., 2004. Genetic signatures of strong recent positive selection at the lactase gene. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 74(6), pp.1111-1120.

-

Enattah, N.S., Sahi, T., Savilahti, E., Terwilliger, J.D., Peltonen, L. and Järvelä, I., 2002. Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia. Nature genetics, 30(2), p.233.

-

Enattah, N.S., Jensen, T.G., Nielsen, M., Lewinski, R., Kuokkanen, M., Rasinpera, H., El-Shanti, H., Seo, J.K., Alifrangis, M., Khalil, I.F. and Natah, A., 2008. Independent introduction of two lactase-persistence alleles into human populations reflects different history of adaptation to milk culture. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 82(1), pp.57-72.

-

Mulcare, C.A., Weale, M.E., Jones, A.L., Connell, B., Zeitlyn, D., Tarekegn, A., Swallow, D.M., Bradman, N. and Thomas, M.G., 2004. The T allele of a single-nucleotide polymorphism 13.9 kb upstream of the lactase gene (LCT)(C− 13.9 kbT) does not predict or cause the lactase-persistence phenotype in Africans. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 74(6), pp.1102-1110.

-

Olds, L.C. and Sibley, E., 2003. Lactase persistence DNA variant enhances lactase promoter activity in vitro: functional role as a cis regulatory element. Human molecular genetics, 12(18), pp.2333-2340.

-

Seppo, L., Tuure, T., Korpela, R., Järvelä, I., Rasinperä, H. and Sahi, T., 2008. Can primary hypolactasia manifest itself after the age of 20 years? A two-decade follow-up study. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology, 43(9), pp.1082-1087.

-

Tishkoff, S.A., Reed, F.A., Ranciaro, A., Voight, B.F., Babbitt, C.C., Silverman, J.S., Powell, K., Mortensen, H.M., Hirbo, J.B., Osman, M. and Ibrahim, M., 2007. Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nature genetics, 39(1), p.31.

-

Swallow, D.M. and Troelsen, J.T., 2016. Escape from epigenetic silencing of lactase expression is triggered by a single-nucleotide change. Nature structural & molecular biology, 23(6), p.505.

Appendix I: my full R code:

Appendix II: Details (sessionInfo) about analysis:

About author

Inga Patarcic is a PhD Student at Berlin’s Institute for Molecular Systems Biology (BIMSB) in the Bioinformatics and Omics Data Science Group. Her major focus of research is gene regulation, disease biology and machine learning. She is an author and initiator of the myDNA R package, shiny app and this blog. Previously, she worked in the field of population genetics (University of Zagreb, Croatia) , ancient DNA (University of Split, Croatia), biomedicine (University of Edinburgh, UK), and biospeleology (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia). She is an active storyteller, science educator, and passionate climber.

Disclaimer

Information shared in this post is for educational purposes only. We do not diagnose or prevent any illness or disease. This post has not been evaluated by the Food & Drug Administration or any other medical body. You must consult your doctor before acting on any content on this post.

In addition, most human traits and diseases are products of interactions of hundreds of genes and variants influenced by many non genetic factors. Thus, SNPs presented in this post are likely only a very small puzzle piece in a large picture of genetic, epigenetic and environmental influences on the development of trait.